Alessia Glaviano

Vogue Italia’s photo editor is the girl to know in the world of photography. She sat down with La DoubleJ to talk about her most memorable shoots, her mentor Franca Sozzani and 20 years at fashion’s style bible.

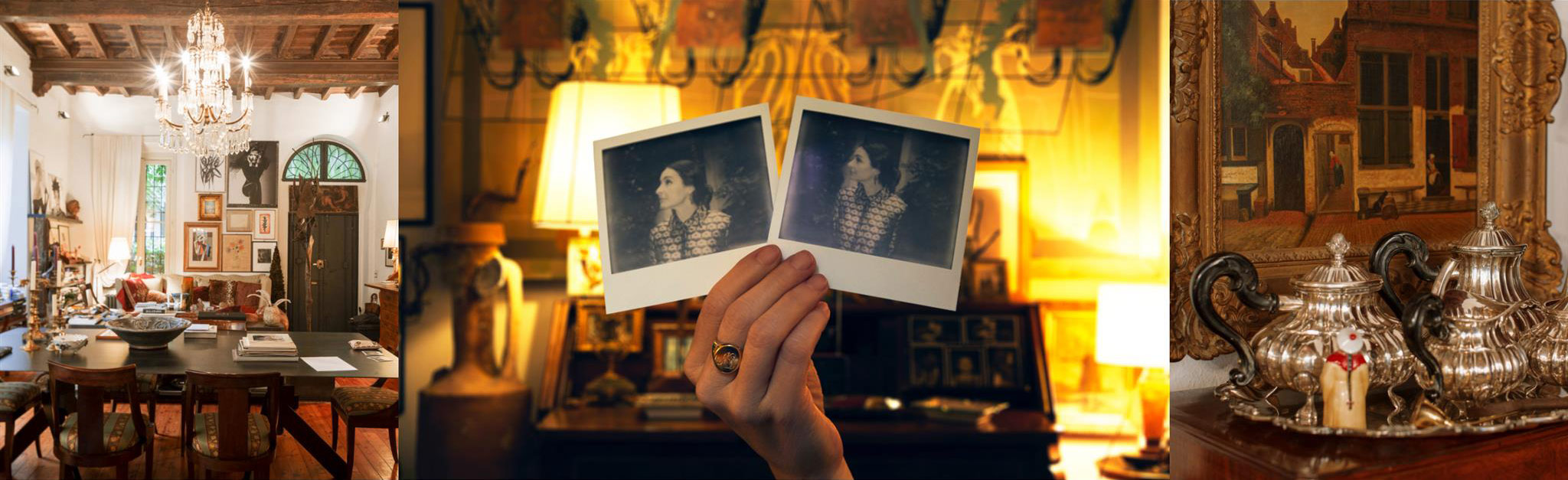

Portrait Photography: Alberto Zanetti — Photography Assistant: Chiara Quadri

Location Photography: Mattia Iotti — Make-up: Francesco Mammone

Words: Laura Todd.

“When I arrived at Vogue, we didn’t even have email – it was basically a billion years ago.”

In 2011, she launched the online platform Photo Vogue, which allows up-and-coming photographers to upload their work in hopes of getting noticed by the likes of Glaviano and her Vogue cohorts. Now, alongside Vogue Italia’s newly installed Editor in Chief Emanuele Farneti she also wears the hat of Brand Visual Director for vogue.it, Vogue Italia’s Instagram and Photo Vogue. From those ventures grew Photo Vogue Festival, the yearly event Glaviano runs and curates in Milan, held from the 16th to 19th of November.

Today, Glaviano is off the clock. She’s curled up on an oversized sofa in her aunt and uncle’s cavernous living room in Milan’s medieval Cinque Vie neighborhood, rolling a cigarette and talking, between drags, about her impressive 18 years at the forefront of fashion and photography. She’s just changed out of her last La DoubleJ outfit and slipped into her daily uniform of a black James Perse t-shirt and dark jeans. “If I like something,” Glaviano explains, “I’ll buy twenty of it and wear it every day. But I actually loved the geometric-print Chemisier dress. I don’t normally wear print,” she continues with a laugh, “but now I think I should start.”

There are a few places one could pick up the thread of Glaviano’s life story. You could start in Palermo, where she was born into a long line of artists: her father is famed fashion photographer Marco Glaviano, whose byline littered the pages of American Vogue, Harper's Bazaar and Vanity Fair from the 1970s well into the 90s. Her great uncle was the influential Italian artist Gino Severini, of Futurist fame; another uncle, renowned sculptor Nino Franchina.

Growing up in such a creative family was “a gift,” she says. “Even if you’re too young and not aware of it and you can't really put it in language or be rational about it, you are still exposed to art. It stays in you and open doors for you. It shapes your vision and informs everything that comes after in your life.”

The family home we sit in is very much a testament to that upbringing. From floor to ceiling the walls are a jumbled patchwork of photographs and paintings accumulated from family and friends: black and white photographs by her father; museum-worthy paintings and sculptures by Severini (in fact, Fondazione Prada recently borrowed a life-size sculpture of Glaviano’s grandmother as a girl for a recent exhibition); Franchina’s wild, abstract constructions. Her place, across town in trendy Porta Venezia, has a similar aesthetic, she insists: “I collect photos and books on photography,” she says, “my house is similar, just on a smaller scale.” But, ever the behind-the-scenes kind of gal, she prefers to keep her own private life far from the photographer’s lens. Alternatively, you could start Glaviano’s story in New York, in the nineties, where she was an assistant at Pier 59, the infamous photo studio — co-founded by her father — that hosted some of the greatest, golden-age-of-magazine shoots. “Everything was over-the-top back then,” she recalls of her time at the studio, “everyone thought they had to be a diva and create tension to get a good shot.”

Or, you could begin in Milan, where she moved in 2001, “a month before 9/11,” she says with a look of horrified relief. At the time, she was unsure of the direction she saw her life going. Not wanting to put her degree in economics to use, a mutual friend set her up on an interview with then Vogue Italia editor Franca Sozzani. There, indeed, is where her story really starts. “I loved Franca,” says Glaviano of her former boss, who passed away in 2016 from cancer, a deeply tragic event the fashion world is still reeling from. “She was a friend, a mentor, a genius.” It was clear, too, that Sozzani saw the potential in Glaviano from early on. She quickly promoted her from her job in production to a role closer to the magazine’s beating heart: “We were doing everything,” Glaviano remembers, “from writing articles to choosing images for the magazine, to researching ideas, to curating exhibitions to designing centerpieces for our dinners. Everything with her was 360 degrees.”

After her experience at Pier 59, photo sets were old hat for Glaviano, but she still speaks in tones of hushed awe remembering the masters at work. “I remember a story we did with Helmut Newton,” she recalls, “you would think, it being Helmut Newton, it would have been a huge production. But we shot it in a hotel in Milan with basically no equipment. It was just him and his Leica and the hotel room lights. He only took two frames for each image. Everything was already in his mind.” She cites Richard Avedon and Steven Meisel as her all-time favorites. The Plastic Surgery issue we did with Meisel was genius, total genius,” she remembers, “he could totally change his style in an instant and still be the best.” But these days, her laser focus is directed towards uncovering new talent, mainly online.

Having started at Vogue in 2001, her career straddled the generation that saw the internet unceremoniously chew up and spit out the publishing industry, which was then left to rebuild itself in a 21st-century image. “When I arrived at Vogue, we didn’t even have email,” laughs Glaviano, “it was basically a billion years ago.” Since then, and much to Glaviano’s credit, Vogue Italia’s online identity has blossomed. “It has given me the chance to explore things I couldn't in the print magazine,” she explains, “you don’t have to deal with just fashion, you could deal with social issues, too.” These days, much of her working life is dedicated to Vogue Italia’s online presence. On a given day she may be devising the strategy for Instagram, writing articles for the website, choosing images for Photo Vogue, or planning the yearly festival. “I look at over 3,000 photos every single day,” she says, “but it never gets old.”

Glaviano’s sustained passion for her work, after so many years, is refreshing to see. But it would be difficult to argue there is anyone more uniquely suited for the job. “A friend of mine once told me the definition of what vision is and it’s something I totally agree with,” she explains, “photography would just be a piece of paper without the coefficient of transformation from reality to someone’s personal vision of it. I think I’m very good at understanding if someone has that vision or not. I get it right away.”